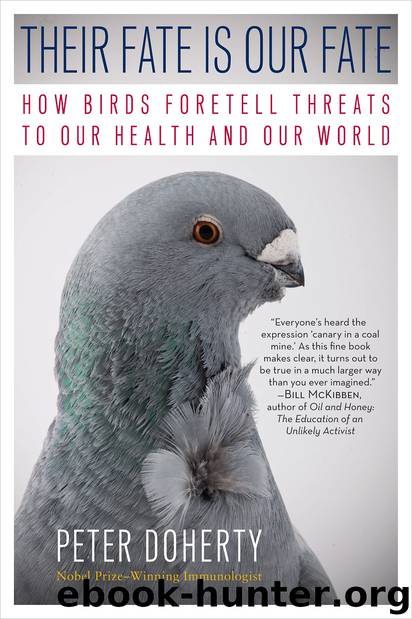

Their Fate Is Our Fate by Peter Doherty

Author:Peter Doherty

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The Experiment

Published: 2013-07-24T16:00:00+00:00

14

Blue bloods and chicken bugs

TRADITIONALLY, ANY NOTION OF good breeding and inheritance was synonymous with the idea of blood lines. That was before the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel’s sweet pea breeding experiments (obscurely published in 1866) led to the founding in 1901 of the science of genetics, and way, way before Watson and Crick had explained the nature and function of DNA. Even so, many still equate blood and heredity, particularly when it comes to thoroughbred horses, dog breeds and aristocrats. You sometimes hear it said that ‘blood will tell’, or ‘blood will out’, which has nothing to do with bleeding, or with murder for that matter.

Over the ages, the principle of hereditary monarchy has depended on the assumption that ‘royal blood’ confers superiority and consequent privilege. But being a blue blood carries no guarantee of genetic superiority in humans, at least so far as disease is concerned. (The idea that royalty and members of aristocratic European families were ‘blue blooded’ probably derives from the fact that, not having to work in the fields, their blue, venous blood was visible through pale, white skin.) The intermittent madness of George III (1738–1820) is thought to have been a consequence of variegate porphyria, a condition that probably came down to him via his ancestor James I of England, also known as James VI of Scotland (1566–1625). And it is certain that Queen Victoria passed on the X-linked gene for haemophilia. Being on the female X chromosome, this disease is only manifest in any XY male who is unfortunate enough to get the abnormal X, while the XX female is protected by the alternative, ‘silencing’, normal X.

The sex chromosome equation is the other way around in birds, with the females being heterogametic (ZW), while the males are ZZ. That means that any Z-linked genetic abnormality shows up in the hen rather than the cock. Haemophiliac birds would not last long, of course, either in nature or in a human-directed breeding program, so the persistence of a Z-linked mutation causing such a severe health defect would simply manifest as the early death of a few females. Even so, sex chromosome linked genetic effects may not be all bad. The Z-linked lutino characteristic in cockatiels (color from yellow to all white) is determined by a disabling mutation in a grey pigment (melanin) gene, but this doesn’t manifest as albinism, because (unlike us) the birds also have yellow pigment genes (psittacins). The mutant melanin gene is recessive, meaning that in a male that has only one copy, it will be ‘silenced’ by the normal Z. Any female bird bred from a lutino male will thus be white and/or yellow, because the cock must have two abnormal Zs, while that will not necessarily be true for the female offspring of a lutino hen (and never the case for the males) when the parent cock has two normal Zs.

Inheritance may thus have good and bad consequences, but can ‘blue bloods’ and favourable ‘blood lines’ really be characterised by

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Periodization Training for Sports by Tudor Bompa(8237)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6683)

Paper Towns by Green John(5163)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4564)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4367)

Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery by Eric Franklin(4199)

ACSM's Complete Guide to Fitness & Health by ACSM(4040)

Kaplan MCAT Organic Chemistry Review: Created for MCAT 2015 (Kaplan Test Prep) by Kaplan(3993)

Introduction to Kinesiology by Shirl J. Hoffman(3753)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3752)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3596)

The River of Consciousness by Oliver Sacks(3587)

Alchemy and Alchemists by C. J. S. Thompson(3501)

Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre(3411)

Descartes' Error by Antonio Damasio(3261)

The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee(3133)

The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee(3085)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(3045)

Kaplan MCAT Behavioral Sciences Review: Created for MCAT 2015 (Kaplan Test Prep) by Kaplan(2972)